- What does RINGO mean by transformation?

RINGO has said that we want to transform global civil society to be able to respond more effectively to the challenges before us. In order to this, we will embark on a process to co-design those elements that we think will be genuinely transformative. The nature of systems change approaches is that we can’t pre-prescribe solutions, but create a format to help build consensus around the solutions that are needed, and create a process to trial these out in practice.

Our transformation dimensions will emerge as part of a series of prototypes that we will collectively invest in as these are identified and agreed by the core team that is convened. Some thoughts around the criteria for these are:

1) That a prototype/innovation will change the practice of multiple organizations and aim to shift the dial on at least one of the key systemic dimensions identified in the RINGO context document, including (but not limited to):

-

- Power and trust

- Diversity and genuine inclusion

- Governance and accountability (both of INGOs and regulatory processes)

- Funding/resources/ownership models

- Role, collaboration, solidarity across civil society (including national and sub-national organisations and social movements)

- Organizational form, including legal forms, size and scale

- Culture, practice and cognition

- Public policy

- Technology

2) Secure significant support as a priority prototype from individuals of the core group and recognised as important from a diverse group of RINGO’s stakeholders.

3) Have at least 2 ARPs (action research pods) willing to lead on building broader connected innovative practice for (un)learning, testing, implementation, assessing.

3) Be trialled and implemented across at least 3 or more national contexts and bridging northern/southern dimensions.

4) Be considered relevant in terms of how it will significantly improve how global civil society works together to combat core external issues, such as closing civic space, inequality or climate change.

5) Be scalable and replicable across multiple organizations and ideally across more than one area of practice (eg. environment, humanitarian, human rights).

- What does RINGO mean by ‘INGO’ and the system?

There is a wide body of academic literature around INGOs. In its simplest form, INGOs are simply organizations that are independent of government that work with an international scope, which could be service or advocacy based (and often both).

Key characteristics:

- Mandate & Spread: Multi-mandated or single-mandated and multi-country presence covering development, environment, human rights, peace-building with established bureaucracy and systems with a focus on service delivery, advocacy and

- Budget: There are small INGOs that raise and spend less than $1 million, to larger ones who can raise beyond $1 bn in consolidated income, raised from a diverse set of funders: foundations, governments and individual donors. RINGO would be aimed at transforming specifically those with a larger scale and reach, however smaller organizations are also part of the transformation picture, so long as they meet other criteria.

- Collaboration: They work in countries with national and local NGOs, CBOs, and/or social movements.

- Scale of operations: They have staff at their headquarters, regionally, in-country and for multi-lateral processes.

For the purposes of RINGO, we are mainly seeking to transform the INGO model that has emerged out of northern/western contexts.

Our work is cross-sectoral: it includes humanitarian and development organizations, alongside human rights, environment and peacebuilding. Issues that have emerged around critiques of INGOs that we have identified (listed in transformation) do not seem to be solely linked to any sub-sector of INGOs. For example:

- Local and international civil society have consistently disagreed with approaches to combatting issues. Environment organizations, for example, have faced conflicts between International conservation groups and local indigenous civil society groups, often being challenged in their approaches.

- Most INGOs, regardless of construct (membership vs other funding model) or focus area, have faced challenges with regards to closing civic space.

- Many INGOs are accountable to their donors, generally situated in the North rather than the global south. Thus accountability models are in universal need of reform.

- Diversity and inclusion challenges have been highlighted within most sectors of INGOs. We need to look at the systemic underpinnings and address these factors beyond the individual or organizational dimension.

We may also choose to learn from new model INGOs if they emerge through our work, for example southern-led organizations or hybrid social movement/INGOs. But these will not necessarily be the subject of our transformative work.

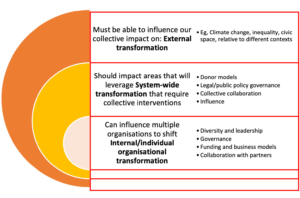

Bringing it all together: We see transformation of the system in three areas: