This article was originally published by Just Ground.

The UN Forum on Business and Human Rights needs an overhaul. As the world’s largest annual gathering on business and human rights, it is an important venue for exchange of ideas and good practice — but one that has not provided sufficient space for rights holder expertise and input.

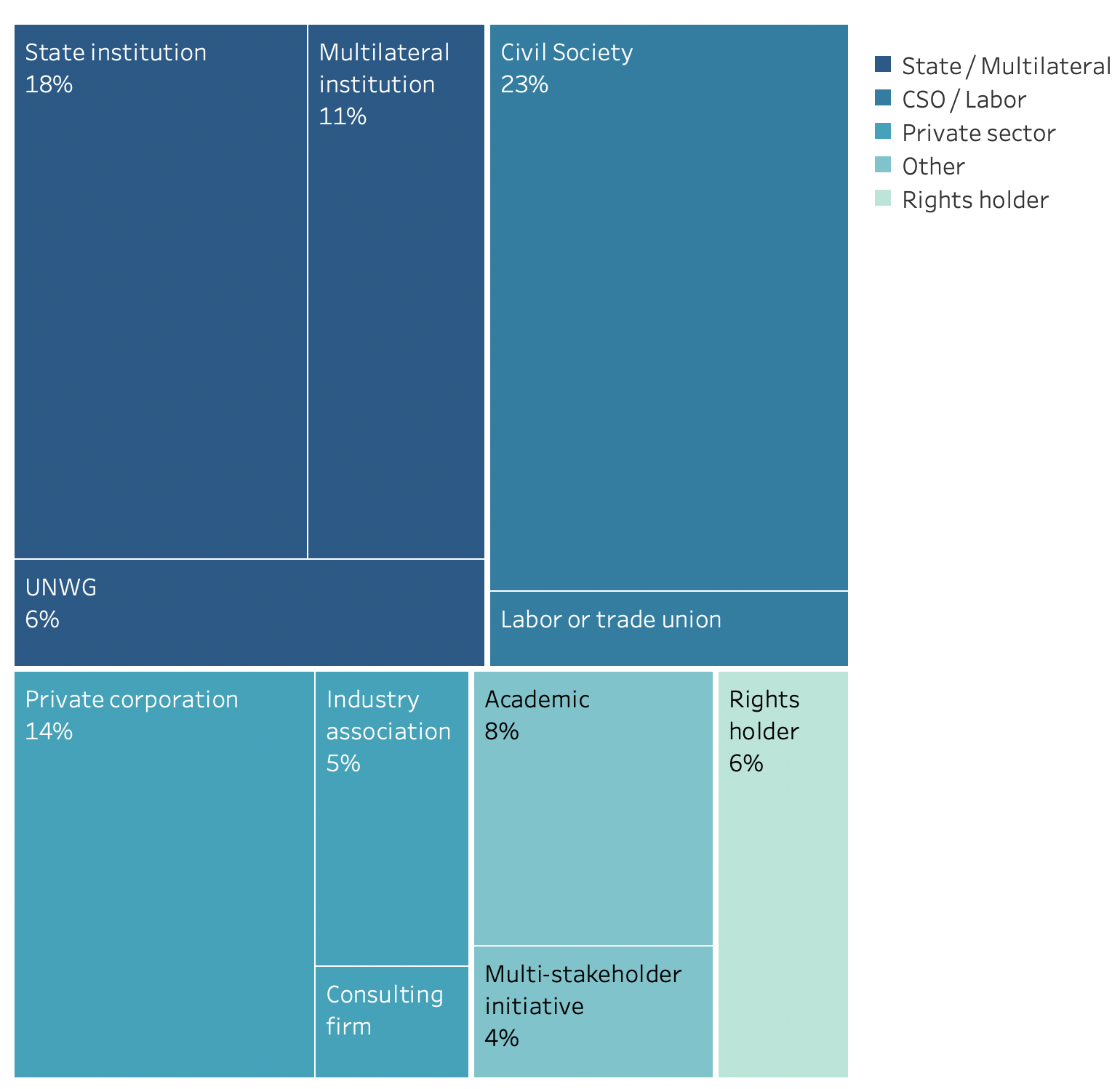

Breakdown of Speaker Groups at the UN Forum, 2018-2021

We cannot hope to advance human rights without the input of rights holders, which is why I am devoting several posts to this topic (with a nod to Tara Van Ho’s series of blog posts on academics at the Forum, which inspired this research). This post will address why it is important to have rights holders as speakers at the UN Forum. The next post will address the breakdown of speaker categories over the past four years of the Forum, the geographic diversity of speakers, and explore potential reasons why rights holders make up the smallest subset of speakers at the Forum. I also hope to hear from rights holders themselves on their impressions of the Forum and how it could be improved. Finally, when the program for this year’s UN Forum is released, I’ll update my figures to see if this year is any better at including rights holder voices (which, it should be, given that this year’s theme is Rights Holders at the Centre).

Methodology

The data was acquired from the UN Forum’s official schedule, which is available online for each year. For the past four years, the Forum has used the same online event platform, which provided a consistent format for comparison across 2018-2021. The information collected for each speaker included:

-

The role they served (moderator or presenter);

-

Country where located;

-

Institutional affiliation provided in their bio; and

-

Speaker category (based on the institutional affiliation and topic).

If a speaker appeared on multiple panels during one UN Forum convening, that speaker was recorded each time, because each panel represents a separate speaking opportunity. I did not include moderators in my calculations, for the reasons that Tara Van Ho states, namely, that a speakers’ role “is to provide expertise, nuance, and clarity about specific issues and to substantively respond to the audience’s questions,” whereas a moderator mainly directs the flow of the presentation. Also borrowing from Van Ho’s approach, the speaker categories were assigned based on the capacity in which the person was speaking. For example, although the UN Working Group on Business and Human Rights (UNWG) has included several academics, they were designated as “UNWG” if they were speaking in that capacity. Similarly, rights holder speakers are those from affected communities, speaking on the issues impacting them.

In total, data was collected on 1,445 speaking opportunities at the UN Forum from 2018 – 2021, including 197 as moderators. Of these, 31 were categorized as “Unclear” due to information missing from the speaker bio. Moderators and those categorized as “Unclear” were excluded from the calculation of the breakdown of speaker categories. If you’d like a deeper dive into the analysis, or want to run some numbers yourself, check out the detailed methodology and the underlying data.

Why This Matters

The UN Human Rights Council, in resolution 17/4, established the Forum on Business and Human Rights to: 1) “discuss trends and challenges” in implementation of the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs); 2) promote dialogue and cooperation; and 3) identify good practices. Rights holders’ perspectives are not only essential to these goals, their presence as speakers underscores their agency and expertise, contributes to accountability, and helps to counter some of the systematic barriers they face.

It’s also common sense that the people impacted by corporate human rights violations hold important contributions to discussions about how to prevent and remediate those harms. The UNWG recognizes this in its concept note for the Forum this year, which calls for a “focus on how the implementation of the UNGPs can be accelerated from a rights holder perspective.” It has also acknowledged in particular that rights holders should be central to any remedy process. This has been echoed in multiple quarters, including the International Commission of Jurists, the roadmap for the next ten years of implementation of the UNGPs, and other voices calling for bottom-up, rights holder-driven approaches.

Nonetheless, the reasons we need to hear from rights holders bear repeating, as it might spur more action by UN Forum organizers, and the business and human rights community more broadly, to ensure that rights holders appear in more panels in the future. With that in mind, I’ve provided some reminders here.

-

Expertise and Innovation – As the only stakeholder group with an existential stake in the outcome of human rights policies and procedures, rights holders know intimately what works and what doesn’t work. Their perspectives are indispensable as a key source of the “good practices” that the UN Forum seeks to identify. Experience has shown that rights holder leadership in design and implementation of human rights monitoring and remediation systems contributes to their success. For example, rights-holder-led initiatives, such as the Fair Food Program, the Bangladesh Accord, Milk With Dignity and the Lesotho Agreement, have proven effective at preventing serious human rights abuses in situations where the top-down approaches of the social auditing industry have failed.

-

Accountability – As Van Ho’s 2016 post on Rethinking the Forum pointed out, “It’s problematic . . . that businesses can come to the Forum and promote themselves as ‘business leaders’ in human rights without having to recognize or own up to their own historical grievances.” Rights holders’ presence on panels can serve an important role in holding corporations’ (and states’) self-congratulatory discourse in check. State or corporate representatives are less apt to focus exclusively on the positive aspects of a recent initiative or policy when a rights holder from the intended beneficiary group has an opportunity to speak to its shortcomings.

-

Dialogue – Businesses can gain a better understanding of rights holders’ perspectives and challenges when they hear from them at the Forum, which in turn has the potential to improve corporate policy and practice. In many cases, corporations may have little incentive to engage directly with rights holders, or they may have huge blind spots on what the issues are or what questions to ask. As the European Network on Indigenous Peoples raised in its 2014 critique of the UN Forum, direct engagement between businesses and rights holders can foster “a collaborative focus” on the “operational steps necessary” to translate human rights standards into practice. [And, as Van Ho has noted, that kind of exchange would be a huge improvement over yet another panel featuring Nestlé presenting its human rights policies without any critique from rights holders or others on its failures on child labor, for example, or water rights.]

-

Epistemic Justice – Marginalization of rights holders at the Forum is a form of epistemic injustice that adds to the injustices they face in struggles to resist and remediate human rights abuses. I have heard directly from rights holders that their knowledge and expertise is discounted in conversations and negotiations, whereas the word of corporate representatives is more readily accepted. The exclusion of rights holders as speakers serves to reinforce this corporate power over knowledge production, by perpetuating oppressive notions on who holds knowledge and what kind of knowledge is valid and credible. This is particularly relevant in the context of access to remedy, where social and cultural values may define rights holders’ perception of loss. In contrast, by recognizing more rights holders as credible experts, the UN Forum has the potential to promote epistemic justice. And everyone stands to gain from hearing and valuing rights holders’ judgment and insight, which are not only necessary for the constructive dialogue and cooperation that the UN Forum seeks to promote, but also essential if we are going to find rights-respecting ways forward.

-

Solidarity and Connection – Having rights holders as speakers at more panels at the Forum creates more opportunities for them to share experiences and draw connections that can nurture collaboration with other groups facing similar situations. This is an important feature of the UN Forum for all of the stakeholder groups, but particularly so for rights holders, as they face greater obstacles – resource constraints, threats to personal safety, lack of leverage – that make these opportunities particularly valuable.

Despite the reasons I’ve listed here on why having rights holders as speakers is so important – and probably others I’ve failed to mention – the UN Forum, at least over the past four years, has consistently sidelined their voices.

In the next post, I’ll explore potential reasons why rights holders have been largely left out. While things may be different this year, with the Forum’s theme on rights holders at the center, I do this with the hope that all UN Forums going forward include far more rights holders as speakers. Their courage, ingenuity and expertise demand nothing less.

NOTE – This has been edited from the original to fix links and a typo.