Rights holder voices continue to be sidelined at the UN Forum on Business and Human Rights. As the world’s largest annual gathering on business and human rights, the Forum is the global platform, established by the UN Human Rights Council, to: 1) discuss trends and challenges in implementation of the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs); 2) promote dialogue and cooperation; and 3) identify good practices. As I have written before, rights holders’ perspectives are not only essential to these goals, their presence as speakers underscores their agency and expertise, contributes to accountability, and advances new ideas. Bottom line, we need to hear from rights holders. So, this year, I am again writing on rights holder representation a the UN Forum — continuing the tracking I began last year.

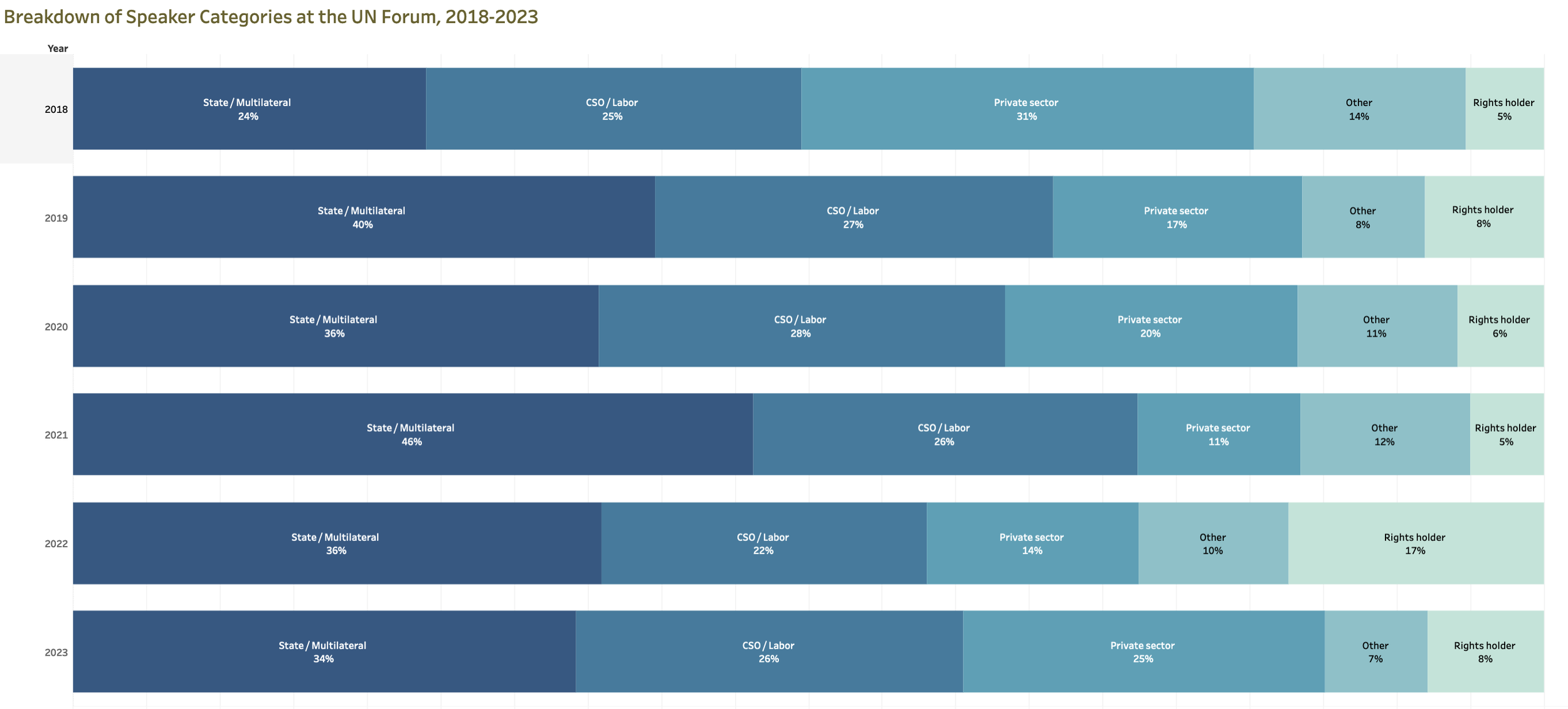

Before we dig into the numbers, a quick note on the methodology. The data was acquired from the UN Forum’s official schedule, which is available online for each year. My 2022 post on the UN Forum speaker breakdown explains the speaker data collection in detail and my second 2022 post covers the session data collection. In addition, the underlying data and detailed methodology are available for those who would like to explore it further. To date, data has been collected on 1,872 speaking opportunities and 311 sessions at the UN Forum from 2018 to 2023.

Why This Matters

People affected by corporate human rights abuses hold important contributions on how to prevent and remediate those harms. No one disputes the importance of rights holder perspectives. From the beginning, the UN Human Rights Council resolution establishing the UN Forum on Business and Human Rights requested that the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) provide the necessary support to convene the Forum, “giving particular attention to ensuring participation of affected individuals and communities.” The UN Working Group on Business and Human Rights (UNWG) — which organizes the Forum with support from OHCHR Secretariat staff — made Rights Holders at the Centre the theme of last year’s Forum. The UNWG has also emphasized the importance of rights holder perspectives on access to remedy, in particular, as has the OHCHR, through its Accountability and Remedy Project report on non-state-based grievance mechanisms, and its report on Remedy in Development Finance. Additionally, the UNWG’s roadmap for the next ten years of implementation of the Guiding Principles called for legislative and policy developments to “emphasize meaningful engagement of rights holders,” and for businesses “to increasingly meaningfully consult with affected groups.”

The Numbers: Rights Holders Sidelined Again

Unfortunately, there is no evidence of these priorities in the breakdown of speakers at the UN Forum this year. Only 8% of the speakers were rights holders, down from 17% last year, and they make up just 8% of the total number of speakers at the UN Forum over the past 6 years.

These charts also show that the majority of the speakers at the UN Forum over the past six years have come from the United States, the United Kingdom and Western Europe. (For the breakdown by region, I used the United Nations’ regional groupings of member states, which includes the United States, United Kingdom, Canada and Australia in “Western Europe and Others.”) And, while this year and last year showed improvement, with over 80% of sessions providing information on whether interpretation was available, over the past five years, slightly over half (54%) of the sessions had that information. Where information was available, interpretation was predominantly provided in English, French and Spanish.

The Need for a More Inclusive Forum

As I’ve explained in a previous post, these cumulative statistics suggest that entrenched disparities in relation to access to power and influence have played a part in sidelining rights holders at the UN Forum. Most of the top countries in terms of sending speakers to the Forum are host states for multilateral institutions (the United Nations in the United States and Switzerland; the European Union in Brussels; the OECD in France) and all of them serve as headquarters for multi-stakeholder initiatives or international human rights NGOs. This trend continued even when the Forum was conducted online during COVID. This suggests that, apart from the travel expense and visa challenges, traditional centers of power impact who speaks at the UN Forum.

Tackling these issues is difficult, and I know that Forum organizers made efforts to have more rights holders as speakers this year. In late August, after the panel topics had been decided, an email circulated, asking for suggestions for rights holders to speak. I know civil society organizations responded with recommendations, and at least one rights holder was selected to speak on a panel through that process, and received CSO support to attend.

But, to echo the rights holders I spoke to last year about the Forum, mere representation is not enough. Rights holders should be invited to shape the agenda, not given four minutes to speak on a predetermined panel after the fact. And they should be welcomed and supported. The rights holder I know who spoke had to secure funding and a visa with just one month’s notice, pull together sufficient warm clothing to survive three days in Geneva weather, and spend more than 2 days traveling there and back — all of which took time and energy from her activism, and none of which is inclusive.

The UNWG’s statements in support of rights holder perspectives reflects that they care about these issues. And the improved rights holder representation at last year’s Forum shows it is at least possible to get more rights holders as speakers on panels. Why not involve them in the design of the Forum as well? A collaborative process that directly involves rights holders serves to model the type of meaningful engagement with affected stakeholders that the UNGPs demand of businesses. It could result in new ways of coming together and provide opportunities to air new ideas and perspectives. What exists now clearly isn’t working for rights holders — and that (still) needs to change.

Photo by Gayatri Malhotra on Unsplash